Underwear is going on underneath, usually, though you never can tell.

When I first began making dolls, nearly thirty two years ago, I dressed them with all the clothes I wore. I was really keen for them to be little people for people, who, unlike the song, were people who didn’t like people but preferred dolls.

I still feel like that, in the main, though I’ve never met a miniaturist or doll person I didn’t get on with, we are mostly coming from the same place even with differing trajectories.

At first I dressed dolls with completely removable clothing, including underwear and socks. To this end I visited a lot of museums and clothing collections, in reality. Thirty two years ago there were no virtual trips round museums, you had to actually go. This was handy because I had a lot of questions I wanted to ask curators.

I went on a couple of tours where the tour conductor was keen to tell the assembled company that they knew for a fact that the people (of which ever era was the subject of the tour) didn’t wear underwear because none had been found.

As I wrote recently, we do know that ancient Romans had toothbrushes; ancient Romans could have grotty teeth just like any other people from history if they didn’t brush them. They also sweated just like any other people in history, which is why the Roman baths are such a massive topic and why the city of Bath is called after the ancient baths. If you are used to being either filthy or washing in a bowl, it is easy to see why putting your whole self in to a restorative hot mineral bath could feel like a cure for all ills.

I was a teacher in the 1970s. I had a flat which had a bath room with a bath but no shower. I bathed every day but in my childhood once a week was considered adequate for everyone. Teaching children who enjoyed the same frequency of bathing, or less, I became very odour aware of which children were clean and which were not. The children were taken once a week to the swimming baths, ostensibly to teach them to swim, which we did, but also to allow the dirt to flow away in a tide of chlorine. In the changing rooms helping children who had clothing with buttons up the back, it was also obvious who had clean, newish underwear and who had inherited hand me downs, with or without holes.

In the eighteenth century children were often sewn into their over clothing during the winter. The zip fastener wasn’t invented in a useable form until 1913, adult clothing was fastened by buttons, hooks and eyes or laces. I had indoor school shoes that were fastened by small, hard, black buttons. To close them you needed a button hook that you inserted through the leather loop on the shoe to pull the button through the loop. It took a while to learn because it was very stiff for little fingers.

A relic of winter sewing persisted into the Victorian age. I learned about it when caring for my mother. Her mother was born in 1888, and continued the practice that had obtained in her childhood. In the spring, when washing and drying lots of clothes out of doors became possible, and children, putting on a spring growth spurt, were released from the clothing they had worn (or been sewn into) they were given what was known as ‘opening medicine.’ This concoction was to aid with opening of the bowels as part of the general clean out. My mother told me of her mother’s surprise appearance with a large jug of what she referred to as lemonade. ‘We,’ muttered my mother darkly, ‘were not fooled.’ All five children had a large glass of this ‘lemonade.’ Although the idea may have been beneficial to health, the simultaneity of administration to a family with just one one-holer earth closet at the bottom of the yard, is questionable wisdom.

They very definitely had undergarments. The survival of undergarmentry, or lack of survival as part of history is difficult to fathom in the textile-rich present. Personal knowledge and historical research fill the gap.

Had you been alive in Tudor times and able to fly an anachronistic aeroplane over England in the late spring or early summer you would have seen many houses surrounded by a patch of blue land. The blue was the flowers of flax, which is used for making linen. Flax is a plant with a massively long stalk which, when the outer tough layer is broken down, is packed with very long continuous fibres, ideal for weaving.

We know that the weaving of linen is a very old skill because of survivals in Ancient Egyptian relics. Mummies are usually wrapped in linen bands. We also know of the weaving of strips of fabric for clothing from anecdotal evidence in the Bible, ‘she wrapped him in swaddling bands and laid him in a manger.’ Some years ago presenter and historian Julian Richards, meeting the ancestors in a TV programme examined a late Roman burial of a young girl which contained artefacts. Among them were what looked like small springs. He wondered what they were. Any weaver could tell you that if you can teach your fingers to twirl fibre round a stick to make a spring, you can spin thread. If you can spin thread, you can weave, if you can weave the simplest item, bands of fabric, you are qualified to get married. The ‘springs’ were the beginnings of spinning and showed that the girl had been buried with her qualifications. A much later badge of ability was the sampler of sewing stitches required to make clothing, of which there are survivors from Georgian times well into the Victorian era.

In the eighteenth century, weaver’s cottages were built with floor to ceiling windows to take advantage of natural light, the high ceilings were bridged with beams over which spun thread could be looped. Weighted with stones or wooden weights with holes in them to tie the threads to and hold them taut, the weaver could take a shuttle, or a ball of spun fibre back and forth, woven between the vertical threads to make long bands.

It is for this reason that spring weddings became traditional. If you marry in May or June, you have time to sow flax seed in your land which will grow and flower in late summer. Then you can obtain the long fibres by rotting the outer casing. You can ‘dew ret’ them by lying them on the fields or ‘water ret’ them in a stream. We know people rotted their flax in streams because of legislation that was passed, stopping the practice because it made water downstream foul and unsuitable for drinking.

Flax that had been obtained was ready for spinning and weaving in the autumn, with woven strips either sewn together into larger pieces of fabric to make new winter clothes or kept as swaddling bands for the baby that would be born in the spring. We have an adjective ‘shiftless’ meaning ‘useless’ which is derived from the mediaeval woman who was so useless she couldn’t make her own shift. This was the long linen undergarment, gathered round the neck on a string that you see above the gown, round the neck, in many portraits of women in mediaeval dress. By Tudor times the pictures make obvious how very fine and gauzy the linen has become. By this time we even have surviving examples of dolls with linen shifts under their gowns, and family portraits with children clutching such dolls. The shift and other undergarments kept the dirt on the skin away from the incredibly expensive over garments on which the decoration was hand embroidered. Those of us old enough to remember embroidery lessons at school know exactly the effort such decoration took. I spent an entire term, aged ten, on the same tray cloth. The teacher, who I hated, took great delight in turning my work over and taking her scissors to it as it wasn’t good enough unless the back looked as good as the front.

Despite the shift and other undergarments, lack of personal hygiene still caused problems with clothes. There used to be a good museum collection of clothes near me, that I was able to examine closely, which included a collection of wonderful embroidered Edwardian clothes made in sweat shops to be worn by the moneyed, and nearly all of them were rotted at the underarms. Elizabethans avoided this problem by having separate sleeves. These were a tube, laced around the top with the laces threaded through a little ruff, called a picadil, over the shoulder. The style of the picadils could change in fashion, the latest being sold in London in the area now known as Piccadilly. This term was also used for the sleeve and ruff supports that framed the face with the latest import, lace, the entire concoction being supported by whalebone, threaded through channels in the undergarments, or ruff props. However fancy the ensemble, the under arms were still able to be exposed to the fresh air, thus saving wear and rot to the fabric which had been hand made at every stage from sowing the seed to embroidery on the cloth.

If it took you that long to make your clothes, nothing would be wasted; linen or wool would be used and worn until it dropped to bits. In Tudor and early Elizabethan times even the bits were used. Men’s breeches got shorter and shorter and puffier. They were stuffed with rags that were known as bombast, giving use the term ‘bombastic’ meaning puffed up with pride and stuffed with rubbish.

There was from mediaeval times, that we know of, maybe earlier, a great trade in second and third hand textiles all over England. I have written of well dressing in Eyam in the Peak District, which continues to this day. Plague arrived in the village in a trunk of second hand clothes from London. The vicar made the brave decision to stop the spread of the fatal disease by making the villagers stay in the village. Most of the villagers died but the plague did not spread. Giving thanks, the children of the village to this day make pictures of fresh flower petals pressed into clay which are used to decorate the wells that provided fresh water to the surviving villagers.

In the past if textiles were valuable, shoes were utterly unaffordable for some. My mother, winning money in a colouring competition as a child in the thirties, near to Jarrow from where the Jarrow marches started, was taken by her mother to the local police station. Here some of the money was given to the Shoeless Children’s Fund, which was run by the police at the time. There are still charities for shoeless children in various parts of the world. I taught a child who only ever wore jelly type sandals and no socks, winter and summer alike, his feet were always red and swollen.

Back to the future of the fifties, I remember my mother polishing the silver with my father’s old string vests. Yes we were posh enough to have silver (it was a teapot, initially, until the antique collecting took hold) but common enough to polish it with the worn out underwear.

This, of course is why there is little surviving evidence of underwear of the past. Even in a horrible condition it was too valuable to throw away. There are some surviving examples among the terribly rich. I have seen with my own eyes, in an antique shop, a pair of wonderfully embroidered separate leg bloomers. The embroidered logo VR would lead you to believe these belonged to Queen Victoria, as would the spiel of the shop owner, however the price was as high status as the reported owner, so I took a good look and left them where they were.

There is no doubt, although not much surviving evidence, that people of the past wore underwear. Today there is great joy to be had in the simple pleasure of wearing new socks that have not gone all crispy underfoot. New knickers, similarly, are so superior to the old ones with the perished elastic.

Bras are another thing altogether. The modern brassiere, arguably began with Caresse Crosby, who invented it in the early years of the First World War, patenting it on February 12th 1914.

Prior to this invention, reportedly draped by Caresse on her ladies’ maid as the model, using handkerchiefs, baby ribbon and safety pins, women supported the upper torso with corsets.

In the costume museum in Bath there are good examples of corsets several hundred years old. The costume museum developed when Bath became a fashionable place for the sickly to take the waters in the hope of a cure. When that didn’t work, accompanying relatives sold the clothes that were no longer needed to help defray the cost of the trip, or the funeral. In the costume museum are examples of very beautiful shifts, some embroidered with blackwork, very effectively worked with black thread on white linen. Over the shifts leather corsets were worn that covered the back, were seamed over the shoulders, scooped down to embrace the rib cage, in the process acting in a supporting role of the shift, gathered over the bosom, the leather being laced at the front, underneath.

As a child I wore the descendant of this type of corset, the Liberty bodice. This wasn’t just a misnomer, it was a total lie. It was reckoned to be healthy because it kept you warm(ish) and was worn from October to March, when it was laundered whether it was slightly grubby, absolutely filthy or not. Old clothing habits die hard.

I stayed with my grandmother most Saturday evenings, so was able to watch her if I was ill during the night getting up to care for me. Out of bed she put her corset on over her nightie, exactly as women for generations before her put their corsets over their shifts. In one swift movement she grabbed the corset from the chair where it reposed overnight and slung it round her, catching the leading edge as it appeared at the side of her, whilst never letting go of the other edge. In a matter of moments she had hooked the two edges together, stood up straight and declared herself able to think.

What you wear does affect the way you think and the way you move. Elizabethan corsets had a slim pocket down the front into which was inserted a busk, a long flat piece of wood, which was sometimes carved or decorated. Whilst supporting the torso and suppressing the stomach effectively it made certain movements difficult. There are a few Elizabethan dances, which look, in paintings, as if the dancers are pogoing, the 1970s punk dance. This was because one of the few movements the busked ladies could achieve was jumping up and down.

There is, of course, another good reason for underwear throughout history, which is feminine hygiene. As a teenager I was the age to benefit from the development of internal sanitary protection for younger women and girls. But at the start of the sixties, going up to my all-girls secondary building, everyone was aware of the Bunny Incinerator located in the downstairs toilets. We wore an elastic belt round the waist from which dangled a hook front and back, hooked on to this was the Dr Whites sanitary pad, which was basically a flat piece of cotton wool enclosed in a gauze. You very definitely needed good thick knickers to keep this item close to you, if it moved around too much, it leaked.

I asked my grandmother what people did before the invention of sanitary pads. These were invented in 1896, so whilst my grandmother, born in 1888 may have been the beneficiary of the invention, she also knew what her mother had done. Every house had a bowl in the scullery, often under the sink, in which rags were soaking. Here we have another good clue as to why underwear of the past appears so infrequently in clothing collections. My grandmother made the point that she and her contemporaries had little choice about whether they had babies or not. Many Victorian women did not have much use for rags, being in a state of permanent pregnancy, Queen Victoria among them, though she was only continuing a long tradition. Queen Anne at the end of the seventeenth century had eighteen pregnancies, though only five births, none of the children surviving into adulthood. It is interesting to contemplate that Queen Victoria was Queen Elizabeth’s great great grandmother, not that far away in history, yet in a different world for women.

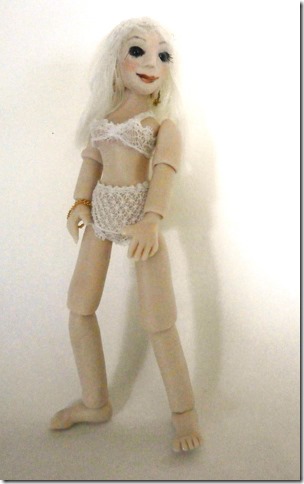

To return to the dolls, I eventually decided that dolls in trousers didn’t need knickers as well, it makes them look lumpy, but dolls in dresses definitely do need knickers because collectors always turn dolls upside down to see what is underneath. And, of course, the dolls sold in underwear with brushable hair have knickers and bras which are glamorous or utilitarian depending on the look of the doll.

I appreciate my underwear of any era, and the dolls look as if they do too.

What do you do if you have no underwear? It seems ridiculous that in the twenty first century, some people only have outerwear, because it covers them and they can’t afford underwear.

There are girls in Africa desperate for an education but unwilling to go to school at certain times of the month for shame because they have no underwear. Since Dr Whites had a good idea in the 1890s there has been progress in slim, effective sanitary pads that stick to underwear. Wonderful, easy, discreet, effective but absolutely useless if you have no underwear.

There are homeless people on the streets of Britain who have no underwear, men, women and teenagers. I cannot imagine how awful it must be to live on the street and sleep in a doorway. Right now, it is sleeting, if I was out in it all the time with just thin doled out clothing and no warm underwear, I don’t know how I would make it through the night, or if I would.

Some years ago I was lucky enough to discover a wonderful charity that I could help with items of clothing I didn’t want. Every now and then I have a good clear out of my bra drawer. I am, and always have been, well endowed. Like all women I fluctuate in weight and size. Women are meant to be stretchy. No stretchy women, no babies, no human race. In my case the stretchiness is evidenced in my bra drawer in the number of bras I have hardly worn because 1) I changed shape in between buying the bra and remembering to wear it. 2) I mail ordered it and forgot to return it in time to get my money back. 3) I bought it in the summer, thinking that red wouldn’t show through my white top. 4) It looked great in the changing room but awful under clothes at home… and so on. The search for the perfect bra which will give me the silhouette of Marie Antoinette, the smoothness of Doris Day and the cleavage of Jane Russell continues.

I am willing to bet I am not the only woman with a drawerful of bra mistakes. It is estimated that 81% of women in the UK are wearing the wrong bra size. I have old favourites including boil wash bras which, when the wires make a bid for freedom and poke out, I recycle. I used to have to throw them away but my local council now collects textiles to recycle. I take the wires out and put them in with the metal.

The good ‘unwearable by me’ ones, the ‘might wear it when I’ve lost half a stone’ ones, the ‘fashionable colour’ ones, the ‘changing room mistakes’, languishing at the back of the drawer, I collect until I have a few, enough to fill a padded postage bag (also usually one I’m recycling). Next time I’m in a well known high street clothing store I add a pack or two of nice new knickers and I post the lot off to the most brilliant charity.

Here it is: www.smallsforall.org

Please do go and have a look and see what wonderful work they do to bring comfort and joy to thousands of people.

I have never (I don’t think) advertised a charity here and I don’t think I ever will again but this is such an easy way to help people for the cost of a pack of knickers and a bit of postage. For this you get the glow of goodness, some space in your underwear drawer, and the knowledge that someone somewhere has dignity and hope because of you.

Ignore what costume museum tours tell you. Of course people in the past wore underwear, shout ‘knickers!’ to misinformation, ‘solidarity!’ to women who need uplifting and send love to Smalls For All, who have to be some of the most inspired recyclers there are. As miniaturists who can do several dozen things with a wooden coffee stirrer, isn’t this right up our street?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~