In a six-street coastal town in Australia I learned the meaning of gratitude from a £5 pom.

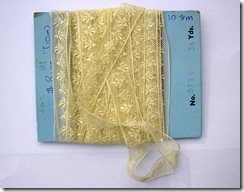

I had ducked into the junk shop out of curiosity and the heat. The mix was as eclectic as you could envisage. Right at the back I found a box of old lace, much of it on the original factory cards, measured in yards. Exclaiming with joy at such treasure trove for a doll dresser I carried those with an adequately small pattern to the counter. There I struck up a conversation with the old chap behind it, who still wore the Cockney accent he’d grown up with as a child in England.

In hard times, post war, as a young teenager he’d chanced everything on a government-sponsored one-way cheap passage in a ship to Australia and thus became one of the immigrants known as a five pound pom. I was very interested; starting life myself in a children’s home I narrowly escaped being a no pound pom. Whether a no pound pom, a five pound pom or a later, richer, ten pound pom, the fate of early child immigrants was often the same; not so many of them lived long enough to breed and populate the land.

The five pound pom had barely disembarked when he fell ill. For many months he lay in a hospital bed. Though ill, he grew, as teenagers do, so that when he was well enough to get up and dressed he found his trousers had turned into shorts that still went round him, as he was so thin, but his feet had grown right out of his shoes.

All the time he was in hospital, a rough and ready priest with a dog collar but always the same homespun trousers and working boots had been keeping an eye on this sickly child from the other side of the world. Now he saw that he was better he asked, “What are your plans, son?”

“Well,” said the five pound pom, “I fancy I’ll get a job on a farm, working the land.”

“How are you going to do that son?” asked the priest, looking at the boy’s long white feet and his short dark shoes. “You can’t work the land barefoot, they won’t let you, we have snakes here, you know. The qualifications you need for land work is boots. Here, you better take mine.” So saying the priest took off his boots and gave them to the boy, who filled up the toes with paper, put the boots on and went and got a job working on the land.

The boy made the most of his chance. He worked and saved until at last he had enough to open a shop. Although the work had been all his, he never forgot his debt of gratitude for the act of charity that got him started. For the next fifty years and counting, to anyone who came into his shop, he told the story of the young five pound pom and a priest who went hospital visiting in his boots but walked home in bare feet.

2 Responses to The story of the five pound pom.