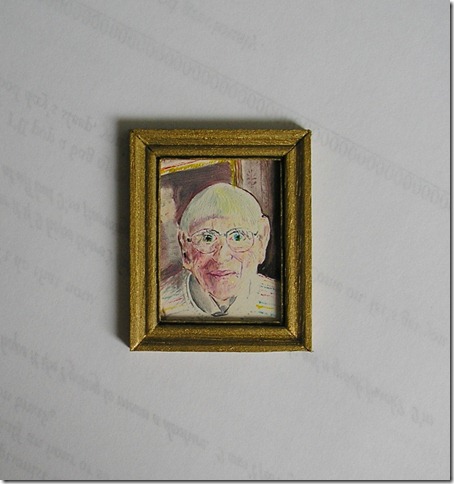

The web manager has corrected the set up problems and I, having little choice of activities, still suffering car crash injuries, have been quietly painting. First here are the pictures you couldn’t see before. This is my father at 91, we were on the way back from his birthday celebrations when we had the crash.

We should all hope to look as good at 91.

The other painting you couldn’t see was the start of Mardol, a street in Shrewsbury. This is how it looked then:

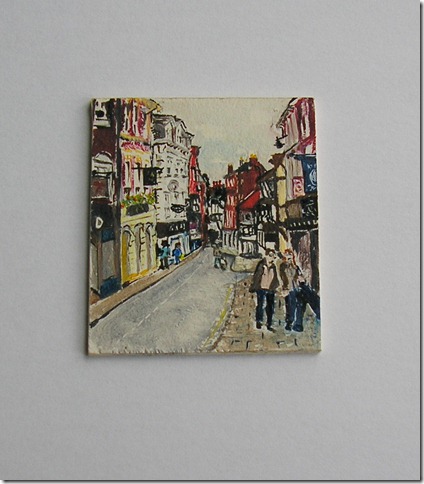

I’ve now finished it, removed the traffic and added some people.

I could have done with seeing it on a brighter day, it was quite damp but not wet enough to make shiny streets. As you may recall, Shrewsbury is one of the Mercian towns founded by Ethelfleda, as part of her defensive strategy against Viking raiders. Although she gets merely a footnote in history books, Ethelfleda is well remembered in the towns she founded. She did so for the protection of the people. The most basic started as an earthwork in a strategic position, enclosed by a wooden fence but she selected so well that nearly all of them are still in use twelve hundred years later.

You might wonder why a town would go out of use or why all old towns are still not lived in, or, if you watch a lot of television programmes featuring archaeologists on distant and windswept moors, why any places are continually inhabited at all. There are many reasons, of which the principle ones are geography and money, which are sometimes the same thing in town planning. Geographically, the very reasons that may lead to settlement in an area, such as fertile soil, for example, can also lead to abandonment of a site, if the resources are exhausted or cut off. A potent example of this is Pompeii, the Roman town that grew to exploit the fertile volcanic soil on top of what the ancient Romans thought was just a an exceptionally well blessed hill with lovely rich well-drained soil you could grow anything in, especially grapes. There are preserved pictures of the hill on walls in Pompeii, it is shown covered in vines, in frames of flower garlands. If you go to visit the town from Sorrento you can take the Circumvesuvio railway and watch from the train windows as market gardeners use the same soil from the volcano’s flood plain, all along the track. Even today, the financial advantages outweigh the dangers of living on an active volcano.

Natural disasters can also lead to complete abandonment of a site. This happened all over Europe during the Black Death, when there were simply not enough people left alive to make the villages work. There are examples near to Warwick in the Burton Dasset hills where the villages were never used again and survive as seven hundred year old ruins, left to crumble into the countryside.

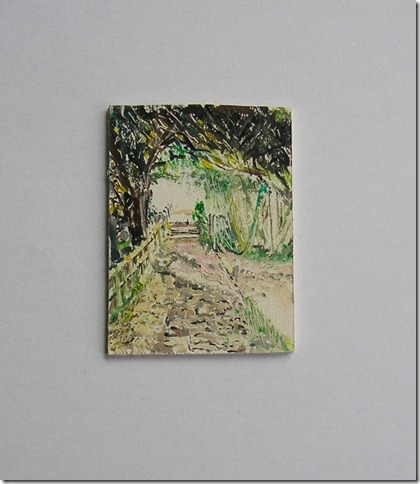

So it is in every country as people exploit the riches of the earth. Just occasionally, a place that has proved good to live in is still so useful and well loved that it remains, unaltered, for twelve hundred years. There is a good example in the Saxon road at the Saxon Mill at Warwick. The watermill exploits the natural course of the River Avon, which has gently carved the hill surrounded by a natural moat, which Ethelfleda found so suitable for the purposes of founding a town. A mile or so outside of the town the Saxon road now leads under the tunnel of trees, across a small wooden bridge into the sunny fields, leading to an old church in the far distance.

If the stones of the road could talk, they could tell you of twelve centuries of travellers by foot and horse, coming across the fields to what became the county town. Initially Anglo Saxons seeking refuge, over the years the travellers would change to local people paying Norman taxes, plaintiffs for justice in the county court, visitors to the castle of the Earl of Warwick, clergy to the churches, the retinue of the Earl of Leicester between here and Kenilworth Castle, where he lived and entertained Elizabeth the First, soldiers on manoeuvres during the Protectorate, eighteenth century sightseers staying in the Castle, people in search of a quiet day out in the country during two World wars and modern tourists thrilled to see you can walk on the same road, on the very same stones, as the daughter of Alfred the Great.

JaneLaverick.com – besotted by history.